Not long after Grandpa returned to King City, on April 9, 1919, he and Grandma had a falling out. This surprised me. The letters they exchanged over the spring, just weeks before his return, were filled with a shared dream, it seemed, of settling down. In time they did make a life together, but it would take nearly ten months—from April, 1919, to January, 1920—to break and repair their wartime romance.

Daddy with Grandma, 1977, on a vacation in Wisconsin.

Many years later, about the time this photograph was taken, Grandma cranked a piece of paper into her portable typewriter and began recording her memories. Grandpa had died–in 1967–and I imagine my father thought it was time for Grandma to fix her life story in print. I pulled out the transcript to see if she wrote about Grandpa’s return.

She did recall Grandpa’s discharge from Camp Grant, and how he didn’t let them know when he’d be home. Her recollection matches Grandpa’s, who wrote in one of his last letters that he didn’t want people to “make a fool of me” when his train came in.

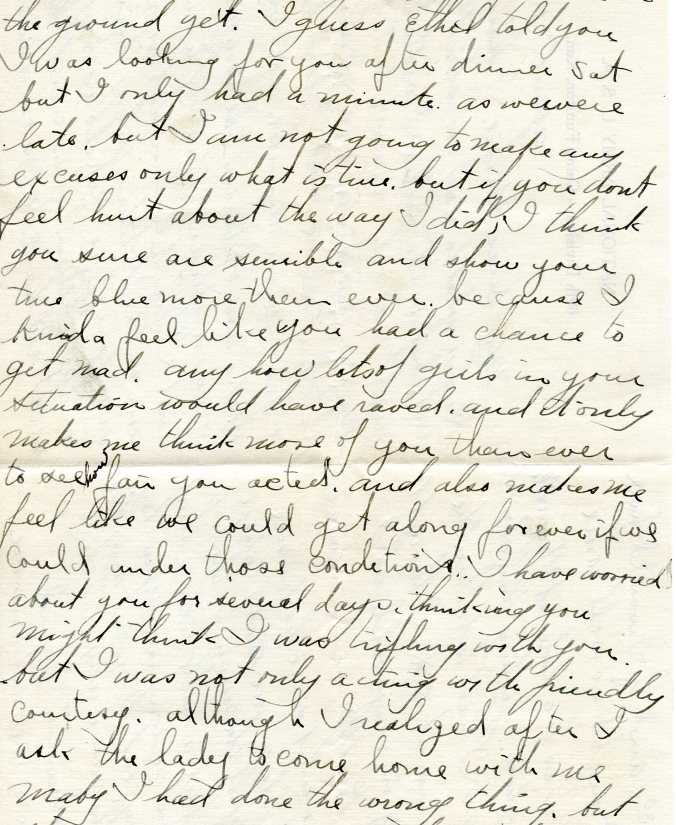

When he reached King City he called me, rented a horse and buggy and came out to our house for dinner. I went home with him for a few days. We dated only a few times when we had ‘a little tiff’ and he went his, and I went mine.

She gave no details on the nature of their quarrel. What could have gone so wrong? I only have two clues.

The first clue is a name I’ve shared on this blog: Stanley Brown. Like Grandpa, he had been drafted for service in Missouri (in Madison, which lies to the east of King City), trained at Camp Funston, and sent to France, where a war injury placed him in the same convalescent facility as Grandpa. It was there, in a hospital complex that served thousands of American soldiers, that the two men first met and discovered that each had the same picture of Grandma tucked in their wallets.

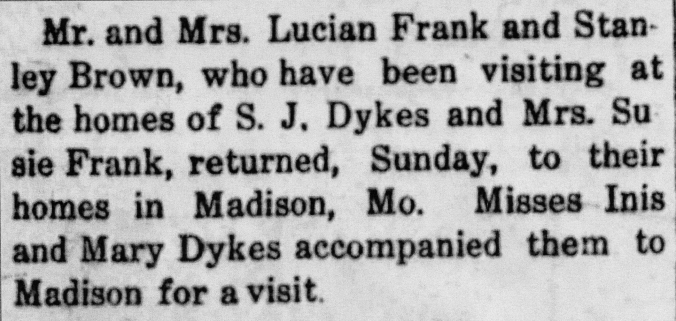

I found a notice in the King City Chronicle, dated August 1, 1919, that mentions a visit by Stanley Brown to King City. In the clipping shown here, the names of Mr. and Mrs. Lucian Frank are those of Grandma’s uncle and aunt (Aunt Susie being the sister of Grandma’s father).

King City Chronicle, 1 August 1919, p. 3.

Grandma vividly recalled a summer visit with her aunt and uncle, one that apparently started before this August event reported in the newspaper.

Early that summer Uncle Dot Franks were up from Madison. They insisted that Mary, me and Dorothy and Sidney go home with them for a two weeks vacation, and they would bring us back. What was supposed to be two weeks lasted most all summer. What a time we had, for they were fine hosts. (. . .) Aunt Susie was also good at seeing that everyone had a date. She didn’t have to worry about me for I began dating a boy I had met there before—Stanley Brown.

Had Stanley Brown crowded into her friendship with Grandpa? Maybe. It’s possible, too, that Grandpa’s war experience had introduced new, unexpected elements into their relationship. He was injured, tired, burdened now with helping his 72-year-old father run a farm. Maybe he was restless, too, “like a bird out of a cage,” the term he used to describe soldiers coming home from France.

Without knowing what caused my grandparents’ quarrel, I think it’s fair to imagine it came along the frayed edges of expectations. The dreams they held during the war, the ones that sustained them over the long months, didn’t materialize at the time of their reunion. The war had changed both the dreams and the dreamers.

That second clue as to what caused the tiff? That’s the subject of my next post.